A Sobering Chronicle of Catholic Persecution Through the Ages

Iconoclastic Fury Illustration - Destruction of ancient christian artefacts and relics by gleeful Calvinist Protestants

The Foundations of the One True Church and the Onslaught Against It

20 Minute Read

To understand the history of Catholic persecution, it is essential first to grasp the basics of Christianity itself, especially for those new to the faith. Christianity began with Jesus Christ, a Jewish teacher and preacher born around 4 BC in Bethlehem, who is believed by Christians to be the Son of God and the Messiah prophesied in the Jewish Scriptures. Jesus taught about love, forgiveness, and the Kingdom of God, performing miracles and gathering disciples. He was crucified by Roman authorities around AD 30 in Jerusalem, but his followers claimed he rose from the dead three days later, an event known as the Resurrection, which forms the core of Christian belief. After his ascension to heaven, his apostles, the twelve closest followers like Peter and Paul, spread his teachings, establishing communities of believers.

From its divine inception, the Catholic Church stands as the original Christian institution, founded by Jesus Christ Himself and entrusted to the apostles. The Early Church Fathers, leaders and writers in the first few centuries after Christ, played a crucial role in shaping and defending the faith. For instance, Clement of Rome, who served as bishop of Rome around AD 88-99, wrote letters emphasising apostolic succession, the idea that bishops trace their authority back to the apostles appointed by Jesus, ensuring the Church's teachings remained pure. Ignatius of Antioch, bishop from around AD 35-107, stressed the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, meaning the bread and wine truly become the Body and Blood of Jesus during Mass, a central Catholic sacrament, or sacred ritual. Polycarp of Smyrna, bishop from AD 69-155, was a disciple of the apostle John and defended core doctrines like the divinity of Christ against early heresies, false teachings that distorted the faith. These saints and martyrs, through their writings and sacrifices, bore witness to a unified faith that later groups like Protestants would fragment, distorting Christianity's essence and enabling waves of persecution. Yet, this truth remains obscured today: Most people are unaware that Catholicism was the first and true Church, with Protestantism arising as a 16th-century schism that sowed division and indirect violence against Catholics. Disturbingly, even in 2025, prominent Protestant apologists like James White continue to undermine this historical foundation by casting doubt on the authenticity of figures like St. Ignatius of Antioch, with recent statements interpreted as questioning his very existence or the genuineness of his letters, which affirm early Catholic doctrines. Unlike many other apologists who engage openly with audiences, White frequently disables comments on his YouTube videos, limiting discussion and debate, which raises questions about openness in theological discourse. If such figures represent leading Protestant voices in 2025, it highlights ongoing challenges in recognising historical Christian truths, as views that dismiss early Church witnesses like Ignatius veer into territory long considered heretical by traditional standards, rejecting the unified witness of the apostles' successors. Persecution of Catholics has manifested not only in overt brutality but through insidious means, propaganda, funding of anti-Catholic groups, and control of narratives by Protestant-dominated media, which has warped the historical record of Christianity. This article traces the grim thread of Catholic suffering from Christianity's dawn to September 2025, revealing how direct massacres and indirect sabotage by forces like Protestantism, Islam, Freemasonry, and atheist communism have claimed millions of lives. Soberingly, modern times witness more Christian deaths, predominantly Catholic, than any prior era, underscoring the persistent reality of this persecution and why Christianity remains fractured and assailed today.

Early Persecutions - From Roman Emperors to the Seeds of Division (1st - 5th Centuries)

The roots of Catholic persecution plunged deep into the Roman Empire, a vast superpower that dominated the Mediterranean world from 27 BC to AD 476, where the undivided Church faced systematic annihilation for upholding Christ's teachings. In this polytheistic society, Romans worshiped multiple gods like Jupiter and Mars, and emperors were often deified, demanding loyalty through sacrifices. Christians, who believed in one God and refused to worship idols or the emperor, were seen as atheists and traitors, disrupting social harmony and blamed for disasters like plagues or fires, as the gods were thought to be angered by their refusal.

Beginning with Nero's scapegoating of Christians for the Great Fire of Rome in 64 AD, waves of terror unfolded. Nero, emperor from AD 54-68, was a tyrannical ruler known for extravagance and cruelty. After the fire destroyed much of Rome, possibly started by Nero himself to clear land for his palace, he shifted blame to Christians. Tacitus, a Roman historian, described the horrors: Christians were arrested, convicted not just for arson but for "hatred of the human race," then executed in gruesome ways. Some were dressed in animal skins and torn apart by dogs, others crucified, and many burned alive as human torches to illuminate Nero's gardens during nighttime spectacles. This set a precedent for viewing Christians as enemies of the state.

The persecution intensified under later emperors, culminating in the Great Persecution under Diocletian from 303 - 311 AD. Diocletian, ruling from AD 284-305, sought to restore Roman unity amid economic and military crises by enforcing traditional religion. He issued edicts ordering the destruction of churches and Scriptures, banning Christian assemblies, and requiring sacrifices to Roman gods. Christians who refused faced imprisonment, torture, or death. Methods included scourging, mutilation, and burning at the stake. Galerius, Diocletian's co-ruler, continued the policy until his deathbed edict in 311 AD tolerating Christianity. Estimates suggest hundreds of thousands perished directly, with indirect tolls from exile and torture amplifying the horror, Christians were fed to beasts in arenas, crucified, or burned alive, their faith tested in public spectacles designed to deter conversions.

Martyrs like Saints Peter, crucified upside down under Nero, Paul, beheaded, and Polycarp, burned at the stake around AD 155 after refusing to swear by the emperor's genius, embodied Catholic resilience. Their deaths affirmed doctrines later challenged by heresies that prefigured Protestant divergences. This era's unity under bishops preserved the faith, but external pressures hinted at future internal betrayals, setting a pattern where opposition to Catholic authority invited destruction.

Medieval Strains and the Reformation's Betrayal - Protestantism as Internal Persecution (6th -17th Centuries)

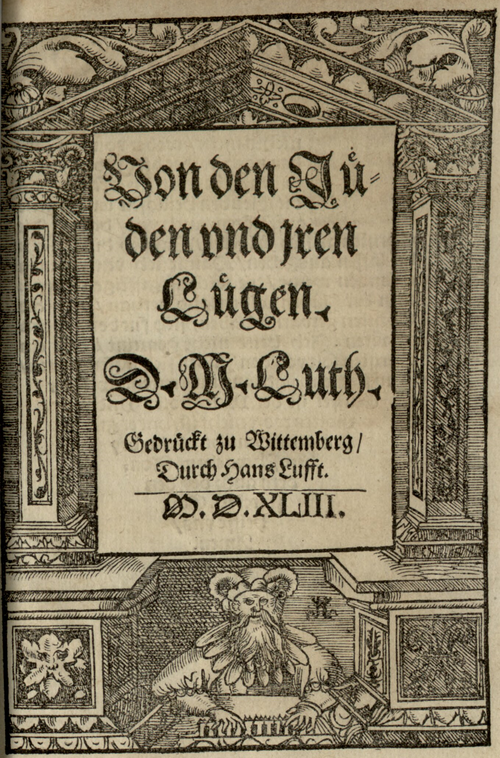

As the Church navigated medieval challenges, a period from roughly AD 500-1500 marked by feudalism, where kings and nobles held power over serfs, and the Church provided spiritual and social structure, the Reformation erupted as a profound act of internal persecution, shattering Christian unity and unleashing horrors upon Catholics. Martin Luther, a German monk born in 1483, initiated this in 1517 with his Ninety-Five Theses, protesting indulgences, Church practices where donations could reduce time in purgatory, a place of purification after death. However, the iconic image of Luther dramatically nailing his Theses to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg, often depicted as a bold public challenge, lacks historical verification and is widely regarded by scholars as a later embellishment rather than fact. The earliest account of this act comes from Luther's associate Philipp Melanchthon in 1547, a year after Luther's death, but Melanchthon was not in Wittenberg at the time and provided no contemporary witnesses to corroborate it. No records from 1517, including Luther's own writings or those of his contemporaries, mention such a nailing; instead, evidence points to Luther mailing the Theses to Archbishop Albert of Brandenburg and other ecclesiastical authorities as a formal scholarly disputation, in line with academic customs of the era. Historians like Erwin Iserloh in 1961 and Peter Marshall argue that the nailing story emerged as a symbolic myth to dramatise the Reformation's origins, but it was neither realistic nor necessary church doors served as notice boards for announcements, yet Luther's intent was private correspondence rather than public spectacle, and the rapid spread owed more to the printing press than any physical posting. This unverified narrative has nonetheless perpetuated a romanticised view of Luther's defiance, obscuring how his actions bypassed Church processes and fuelled division. Luther's ideas, spread by the printing press, emphasised sola scriptura, the notion of the Bible alone as the ultimate authority, rejecting papal tradition, and challenged the sacraments, reducing them from seven to two.

Yet, this principle of sola scriptura, so central to Protestantism, finds no explicit endorsement in Scripture itself, which is a profound irony for those who uphold it as the sole infallible rule of faith. Nowhere does the Bible declare that it is the exclusive source of divine revelation, devoid of the need for apostolic tradition or the interpretive authority of the Church established by Christ. On the contrary, passages such as 2 Thessalonians 2:15 instruct believers to "stand firm and hold to the traditions which you were taught by us, either by word of mouth or by letter," affirming the equal value of oral and written teachings from the apostles. Similarly, 1 Timothy 3:15 describes the Church as "the pillar and bulwark of the truth," indicating its role in safeguarding and interpreting revelation, not Scripture in isolation. The canon of the Bible itself was discerned through Church councils in the late fourth century, relying on tradition to determine which books were inspired, a process that sola scriptura cannot account for without circular reasoning. Early Christians operated for centuries without a complete New Testament, relying on the oral teachings and authority passed down from the apostles, as evidenced by the Church Fathers. This absence of biblical support for sola scriptura exposes its foundational flaw, as it elevates personal interpretation over the unified Magisterium, leading to the fragmentation of Christianity into thousands of denominations (approximately 49,000 as of 2025 projections) and enabling the persecutions that followed.

However, Luther did not pursue his grievances through the established channels of the Church, which would have involved formal theological debates, appeals to bishops, or participation in ecclesiastical councils, processes designed to maintain unity and resolve disputes internally. Instead, on October 31, 1517, he disseminated his Theses by mailing them to superiors such as Archbishop Albert of Brandenburg while arranging for them to be printed and circulated widely across Germany. The rapid printing, thanks to Johannes Gutenberg's invention around 1440, bypassed hierarchical oversight. Within weeks, thousands of copies circulated, sparking public uproar and uncontrolled discussions among laity and scholars alike, without awaiting official Church response or reform. This direct appeal to the masses inflamed divisions, as it circumvented the Magisterium, the Church's teaching authority vested in the Pope and bishops, and invited secular princes to exploit religious tensions for political gain.

Even when the Church did engage Luther in formal debates post-Theses, the outcomes only accelerated his condemnation, yet his movement persisted due to its already viral momentum. For instance, at the 1518 Heidelberg Disputation, Luther presented his theology but faced scrutiny. More significantly, the Leipzig Debate of 1519 pitted Luther and his colleague Andreas Karlstadt against Johann Eck, a skilled Catholic theologian from Ingolstadt. Held at Pleissenburg Castle in Leipzig under Duke George of Saxony, an opponent of Luther, the debate covered free will, grace, indulgences, purgatory, penance, and papal authority. Eck strategically shifted focus to Luther's views on the Pope, forcing him to admit that church councils could err (referencing the Council of Constance's condemnation of Jan Hus, whom Luther defended) and that Scripture alone sufficed for doctrine. While no formal winner was declared, Eck's arguments exposed Luther's positions as diverging from Catholic orthodoxy, leading many observers to view Luther as defeated in upholding traditional authority. This prompted Pope Leo X's 1520 bull Exsurge Domine, condemning 41 of Luther's errors and threatening excommunication, which followed in 1521. At the Diet of Worms in 1521, Luther famously refused to recant, stating, "Unless I am convinced by Scripture and plain reason... I cannot and will not recant," resulting in his outlaw status. Despite these "losses" in ecclesiastical terms where his ideas were deemed heretical, the ball was already rolling: Widespread printing had popularised his Theses, gaining support from German princes like Frederick the Wise, who protected him, and the laity disillusioned with Church corruption, allowing the Reformation to spread unchecked.

In a modern analogy, Luther's approach is akin to a dissatisfied employee in a large corporation skipping internal HR protocols or management discussions and instead posting a scathing manifesto on social media platforms like Twitter or Reddit, where it goes viral, inciting widespread backlash and chaos without allowing the organisation a chance to address the issues formally. Such a tactic, while amplifying the message, often leads to escalation rather than resolution, much like how Luther's printing press strategy fueled the Reformation's violent upheavals rather than orderly reform.

This ignited conflicts like the Peasants' War of 1524-1525. In the Holy Roman Empire, peasants, oppressed by heavy taxes, serfdom, and noble exploitation amid economic hardship from inflation and enclosure of lands, drew inspiration from Luther's teachings on spiritual equality. They demanded abolition of serfdom, fair taxes, and rights to hunt and fish, as outlined in the Twelve Articles. Luther initially sympathised in his "Admonition to Peace," but as violence escalated, with peasants sacking castles and monasteries, he condemned them harshly in "Against the Murderous, Thieving Hordes of Peasants," calling for princes to slaughter them. Nobles, led by figures like Philip of Hesse, crushed the revolt with brutal force, massacring up to 100,000 peasants in battles like Frankenhausen, where leader Thomas Müntzer was captured, tortured, and beheaded. Horrors included summary executions, villages burned, and families starved, highlighting how Reformation ideas fueled social chaos but turned against the poor when threatening order.

Sack of Magdeburg 1631

The Thirty Years' War from 1618-1648 was even more devastating. Sparked by the Defenestration of Prague, where Protestant nobles threw Catholic officials from a window in Bohemia, protesting Habsburg Catholic rule under Ferdinand II, it escalated into a Europe-wide conflict involving religion, territory, and power. Catholics, led by the Holy Roman Empire, Spain, and Austria, faced Protestants backed by Sweden's Gustavus Adolphus, France under Cardinal Richelieu (ironically Catholic but anti-Habsburg), and Denmark. Battles like White Mountain (1620) saw Catholic victories, but horrors abounded: famine from scorched-earth tactics, plagues killing millions, and atrocities like the Sack of Magdeburg in 1631, where 20,000-30,000 civilians were massacred, raped, and burned by Imperial troops under Tilly. An estimated 4-8 million died overall, many Catholics in Protestant raids on churches and villages, with populations in some German areas dropping 50 percent from war, disease, and starvation.

Protestants were instrumental: In England, Henry VIII, king from 1509-1547, broke from Rome in 1534 over his divorce from Catherine of Aragon, executing Catholics like Thomas More, chancellor and saint, beheaded in 1535 for refusing the Oath of Supremacy. Calvinists in Switzerland under John Calvin burned dissenters like Michael Servetus in 1553 for heresy. In France, the Wars of Religion (1562-1598) saw Huguenots, French Protestants, clash with Catholics, culminating in the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre of 1572. Amid tensions after the wedding of Protestant Henry of Navarre to Catholic Margaret of Valois, Catholic mobs, encouraged by Queen Mother Catherine de' Medici and King Charles IX, slaughtered 2,000-3,000 Huguenots in Paris, spreading to provinces with up to 70,000 deaths total. Horrors included mutilations, drownings, and bodies dragged through streets, though the article frames reciprocal violence targeting Catholics en masse in broader conflicts. This schism damaged Christianity wholly by rejecting sacraments, promoting individualism via sola scriptura… Strikingly, Protestantism mirrors Islam in its anti-Catholic stance, both reject tradition, hierarchy, and iconography, viewing Trinitarian Catholicism as aberrant. Ottoman alliances with Protestants against Catholic Habsburgs during 16th-century wars exemplified this, amplifying mutual assaults on the Church. The Reformation's legacy: Millions in direct casualties and untold indirect losses through spiritual fragmentation.

The Plight of Irish Catholics: A Stark Example of Protestant Persecution Among the most poignant illustrations of Protestant-led persecution against Catholics is the enduring suffering of the Irish people, whose faith became a target for systematic oppression under English Protestant rule, extending from Ireland to the Americas and involving harsh economic exploitation, including widespread indentured servitude. Beginning in the 16th century with Henry VIII's imposition of Protestantism on Ireland, English forces under leaders like Oliver Cromwell in the 1640s and 1650s conducted brutal campaigns, including the conquest of Ireland, where Catholic lands were confiscated and redistributed to Protestant settlers in "plantations." Cromwell's siege of Drogheda in 1649 saw thousands massacred, with priests and civilians slaughtered in churches, symbolising the intent to eradicate Catholicism. The subsequent Penal Laws, enacted from 1695 onward, stripped Irish Catholics of rights: they could not vote, hold public office, own land freely, educate their children in the faith, or practice openly, reducing them to poverty and subjugation under Protestant landlords. This legal framework, lasting until Catholic Emancipation in 1829, fostered famines like the Great Famine of 1845-1852, where over a million died from starvation and disease amid potato crop failure, exacerbated by British policies that continued exporting food from Ireland while Catholics suffered.

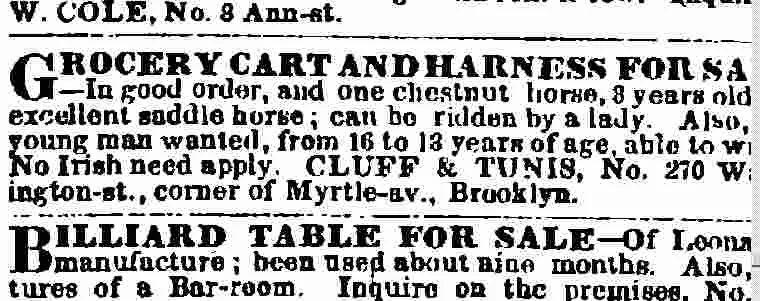

Authentic 1854 newspaper ad from The New York Times explicitly stating "No Irish Need Apply," exemplifying job discrimination against Irish Catholics in Protestant America.

Irish Catholics also endured extensive indentured servitude, a form of bonded labour where tens of thousands were transported to English colonies in the Caribbean and North America from the 17th century, often involuntarily as prisoners of war, rebels, or the impoverished. While distinct from the lifelong chattel slavery inflicted on Africans - indenture typically lasted 4-7 years and offered eventual freedom the conditions were often brutal, with high mortality from overwork, disease, and abuse on plantations. Historians estimate 50,000-100,000 Irish were sent as indentured servants, many as a result of Cromwellian deportations or economic desperation fueled by persecution, making them one of the largest groups subjected to this exploitative system in the early Atlantic world. This hardship persisted in America, where Irish Catholic immigrants fleeing famine in the 19th century faced virulent anti-Catholic nativism from Protestant-majority societies. Groups like the Know-Nothings propagated fears of papal conspiracies, leading to riots such as Philadelphia's 1844 Bible Riots, where churches were burned and dozens killed. Employment discrimination was rampant, with signs reading "No Irish Need Apply" appearing in job advertisements and storefronts, barring Catholics from work and confining them to menial labour. Even organisations like the Ku Klux Klan targeted Irish Catholics with violence and intimidation well into the 20th century. These patterns reveal how Protestant persecution was not confined to Europe but permeated the New World, systematically marginalising Catholics through violence, legal barriers, and economic exclusion, contributing to generations of suffering and diaspora.

A 1862 lyric sheet from a song capturing the discrimination against Irish immigrants, reflecting the era's anti-Catholic bias in employment.

Anti-Irish political cartoon depicting an Irishman as a drunken brute with gunpowder, perpetuating stereotypes that justified persecution of Catholic immigrants

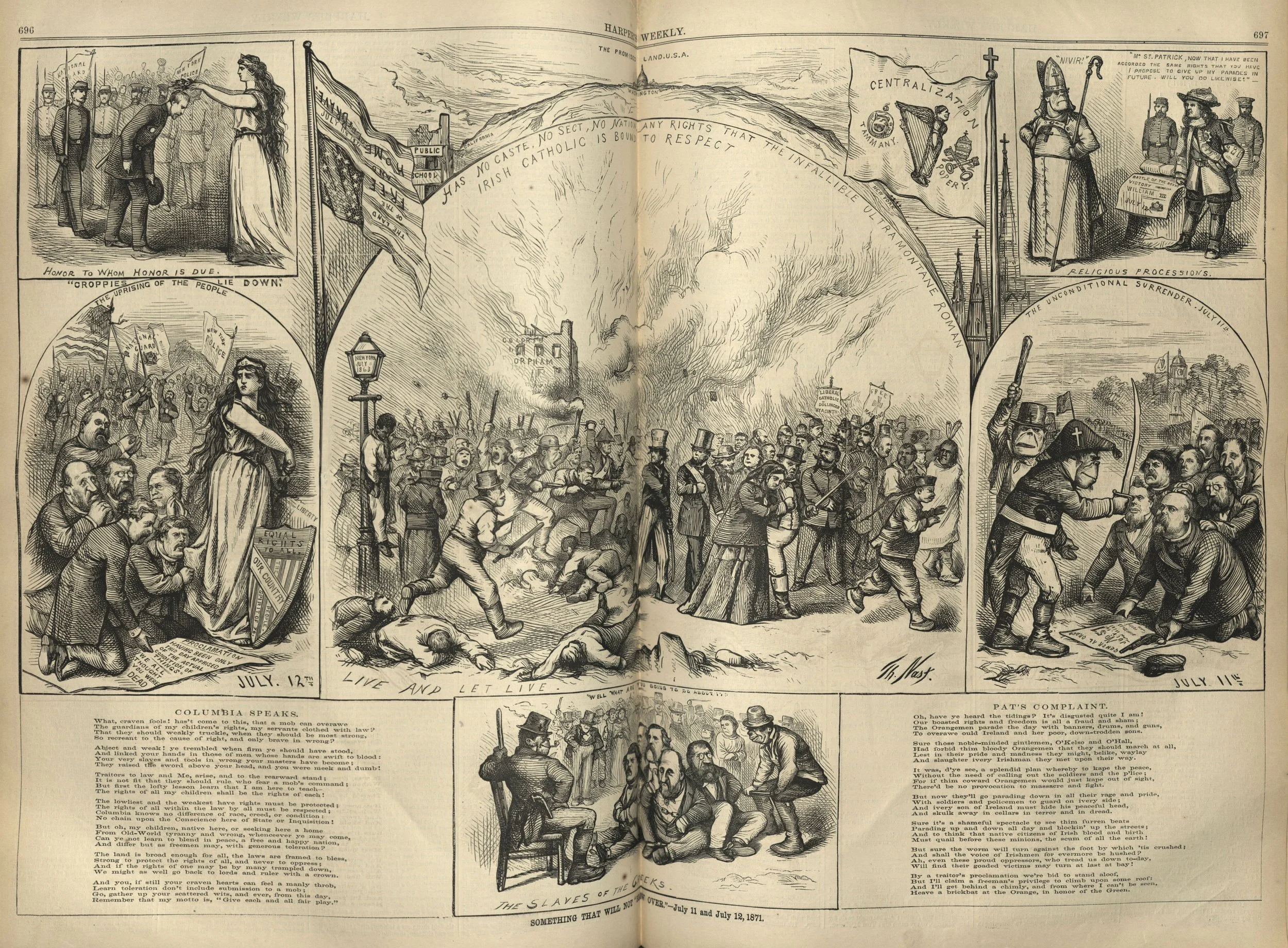

Thomas Nast's double-page illustration depicting the Orangemen's Riots, with vignettes of violence, a hanged African American, and a Catholic cleric portrayed negatively, reflecting Protestant incitement and anti-Catholic bias in New York

Enlightenment Shadows and Hidden Alliances - Freemasons, Propaganda, and Protestant Funding (18th -19th Centuries)

The Enlightenment, an 18th-century intellectual movement emphasizing reason, science, and individual rights, with thinkers like Voltaire and Rousseau challenging traditional authority including the Church, veiled new persecutions, with anti-Catholic networks thriving under Protestant influence. Freemasonry, a secretive fraternal organization originating in 1717 England with Protestant roots, harbored prominent Protestants advancing anti-clerical agendas. It promoted rationalism over faith, viewing the Church as superstitious, and influenced revolutions. The French Revolution of 1789, sparked by economic crisis, inequality under King Louis XVI, and ideas of liberty, equality, fraternity, turned violently anti-Catholic. The National Assembly confiscated Church lands, imposed the Civil Constitution of the Clergy in 1790 forcing priests to swear loyalty to the state, leading to schism. During the Reign of Terror (1793-1794) under Robespierre, thousands of clergy were executed by guillotine, drowned in "noyades" in Nantes, or shot in mass killings. Over 2,000 priests and nuns perished, churches desecrated, turned into "Temples of Reason." Horrors included the September Massacres of 1792, where mobs slaughtered imprisoned clergy, and Vendée uprising suppression, killing 200,000 Catholics resisting secularism.

Violence (via the Know-Nothings) peaked in Philadelphia's 1844 riots: After rumors of Catholics removing Bibles from schools, mobs burned two churches, a seminary, and homes over four days, killing at least 14, injuring dozens. In Louisville's "Bloody Monday" 1855, election-day riots killed 22, with churches and neighborhoods torched. The Ku Klux Klan, founded 1865, perpetuated anti-Catholic violence into the 20th century, lynching and intimidating immigrants. Propaganda painted Catholics as disloyal papists, influencing policies like school funding bans. Protestant-dominated media perpetuated this bias, erasing Catholic primacy and fostering ignorance. Indirect casualties: Cultural erasure affecting millions.

The Atheist Onslaught - Communism, Holodomor, and 20th-Century Horrors (20th Century)

Atheist communism, heir to Reformation individualism and Enlightenment secularism, unleashed unprecedented terror on Catholics. Communism, an ideology developed by Karl Marx in the 19th century advocating classless society through revolution, was atheistic, viewing religion as "opium of the people" oppressing workers. Under Joseph Stalin, Soviet leader from 1924-1953, this led to militant campaigns against faith.

The Holodomor (1932 - 1933), Stalin's engineered famine in Ukraine, killed 3 - 5 million, targeting Christian peasants amid church destructions and clergy executions under militant atheism, part of Soviet persecutions claiming 12 - 20 million Christian lives. Ukraine, largely Orthodox and Catholic, resisted collectivization, forced farm mergers. Stalin exported grain while blocking aid, causing starvation horrors: families eating grass, corpses in streets, cannibalism reports. Churches closed, priests shot or sent to gulags, as Stalin promoted "scientific atheism" to eradicate religion.

Globally, Mexico's Cristero War (1926 - 1929) saw 90,000 - 250,000 deaths resisting anti-Catholic laws under President Plutarco Calles, who closed churches, banned public worship, and executed priests. Cristeros, Catholic rebels shouting "Viva Cristo Rey," fought government forces in guerrilla warfare, facing atrocities like hangings and firing squads. The Spanish Civil War (1936 - 1939) claimed 6,800 clergy in the Red Terror by Republican communists and anarchists against Franco's Nationalists. In zones like Barcelona, priests were hunted, churches burned, nuns raped and killed, with bodies desecrated. Regimes in China under Mao and Cuba under Castro added millions more through suppression. Statistic: Over 45 million of 70 million total Christian martyrs died in the 20th century, surpassing all prior centuries.

Modern Persecution - More Horrific Than Ever (21st Century - 2025)

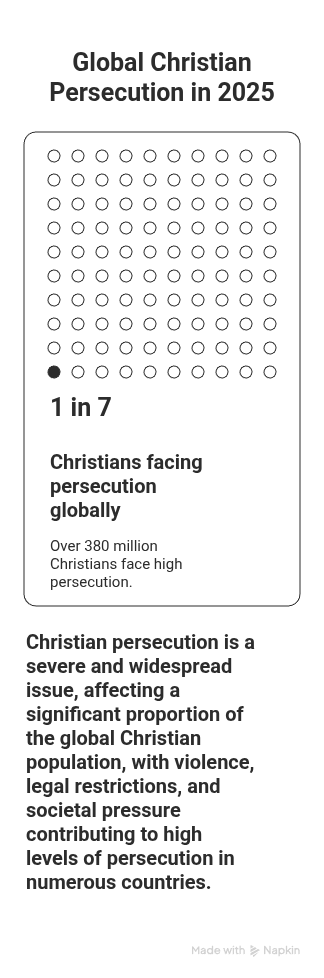

Today, the scale eclipses history: Open Doors' 2025 World Watch List publishes the annual ranking of the 50 countries where Christians face the most severe persecution based on factors like violence, legal restrictions, and societal pressure. The 2025 edition reports over 380 million Christians, many Catholic, facing high or extreme levels of persecution globally, a staggering figure representing about one in seven Christians worldwide. This includes restrictions on practicing faith, such as bans on public worship, forced conversions, or discrimination in employment and education. Annual killings are estimated at 4,400 - 5,000 from 2023 -2025, with many victims Catholic, mainly in countries like North Korea, Somalia, Nigeria, and Pakistan. These numbers outpace Roman-era rates when adjusted for global population growth while ancient persecutions killed thousands over centuries in a world of millions, today's toll affects a far larger proportion relative to the 2.3 billion Christians alive now.

For context, in North Korea, under the Kim regime's Juche ideology of self-reliance blended with state atheism, Christianity is viewed as a Western threat. Underground churches operate in secret, with discovery leading to labor camps, torture, or public executions; entire families are punished for one member's faith, with reports of Christians crushed under steamrollers or used for medical experiments. In Somalia, al-Shabaab militants enforce strict Sharia, targeting Christians as infidels; converts from Islam face beheadings or stonings, with communities isolated and aid blocked. Nigeria sees Islamist groups like Boko Haram, founded in 2002 by Mohammed Yusuf to establish an Islamic state, attack Christian villages, killing thousands in raids, abductions, and bombings since 2009. Notable horrors include the 2014 Chibok kidnapping of 276 schoolgirls, many Christian, with survivors recounting forced conversions, rape, and slavery; ongoing attacks in Borno State involve burning churches, mass shootings at worship services, and displacing millions into camps where starvation looms. In Pakistan, blasphemy laws under Section 295-C of the Penal Code, enacted in 1986 under Zia-ul-Haq's Islamization, prescribe death for insulting Muhammad. False accusations lead to mob violence; cases like Asia Bibi, a Catholic mother acquitted in 2018 after eight years on death row for allegedly blaspheming during a water dispute, sparked riots demanding her hanging. Mobs have lynched Christians, burned homes, and attacked churches, as in the 2023 Jaranwala incident where over 80 Christian homes and 19 churches were torched over unproven blasphemy claims.

Islamist groups echo Protestant iconoclasm, the Reformation-era destruction of religious images and statues deemed idolatrous, as seen in Calvinist attacks on Catholic art; similarly, extremists like ISIS demolish churches and crucifixes, viewing them as shirk (polytheism). Protestant media bias persists, underreporting Catholic suffering Western outlets often frame Nigerian violence as "farmer-herder clashes" rather than targeted anti-Christian jihad, or downplay Vatican alerts on global martyrdom. Recent Vatican reports, such as Aid to the Church in Need's biennial study or the Pontifical Foundation's documentation, note surging martyrs, with over 1,600 new cases in recent years, including priests killed in Mexico amid cartel violence or nuns abducted in Haiti. These patterns reveal how ancient enmities evolve, with Catholics bearing disproportionate burdens in a world where faith remains a flashpoint for violence.

Sources

To make this article "bullet proof" against scrutiny, the following compiles all key sources based on the article's content. All links were verified as of September 22, 2025, and confirmed to load with relevant content from credible historical, academic, or Catholic sites.

Primary Sources and Historical Documents

These include original texts or direct accounts referenced in the article.

- Tacitus on Nero's Persecution - Roman historian's account of the Great Fire of Rome and Christian scapegoating.

Read on Livius.org - Diocletian's Edicts Against Christians - Primary sources on the Great Persecution.

Read on FourthCentury.com - Martin Luther's Ninety-Five Theses - Full text of the document sparking the Reformation.

Read on Luther.de - Twelve Articles of the Peasants - Manifesto from the Peasants' War.

Read PDF on GHI-DC - Account of the Sack of Magdeburg - Eyewitness description from the Thirty Years' War.

Read on GHI-DC - Oath of Supremacy (Henry VIII) - Text related to Thomas More's execution.

Read on Wikipedia (Primary text excerpts) - John Calvin on Michael Servetus - Historical details of the trial and burning.

Read on Wikipedia - St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre Accounts - Historical descriptions.

Read on Britannica - Protestant-Ottoman Alliances - Historical context of Turco-Calvinism.

Read on Wikipedia - Cristero War Testimonies - Accounts of anti-Catholic violence in Mexico.

Read on Wikipedia - Red Terror in Spanish Civil War - Details on clergy killings.

Read on Wikipedia

Secondary Sources and Analyses

These provide historical context, statistics, and interpretations.

- James White on St. Ignatius - Controversy over authenticity claims.

Read on Patheos - Sola Scriptura Not in Bible - Catholic arguments against the principle.

Read on Catholic.com - French Revolution Anti-Catholicism - Reign of Terror details.

Read on IWP.edu - Know-Nothings and Philadelphia Riots 1844 - Nativist violence.

Read on Philadelphia Encyclopedia - Bloody Monday Louisville 1855 - Anti-Catholic riots.

Read on Wikipedia - KKK Anti-Catholic Violence - Historical overview.

Read on Wikipedia - Holodomor Famine - Stalin's policies in Ukraine.

Read on History.com - 20th Century Christian Martyrs Statistics - Estimates of killings.

Read on Gordon Conwell - Open Doors World Watch List 2025 - Persecution rankings.

Read on Open Doors - North Korea Christian Persecution - Details on regime policies.

Read on Wikipedia - Somalia al-Shabaab Attacks - Violence against Christians.

Read on Open Doors - Nigeria Boko Haram Chibok Kidnapping - 2014 incident details.

Read on Wikipedia - Pakistan Blasphemy Laws - Asia Bibi Case - Overview and details.

Read on BBC - Jaranwala Attack 2023 - Mob violence against Christians.

Read on Wikipedia - ISIS Destruction of Churches - Iconoclasm in Iraq/Syria.

Read on Oxford Academic (PDF available) - Protestant Media Bias on Persecution - Underreporting claims.

Read on Premier Christianity - Vatican Reports on Modern Martyrs - Aid to the Church in Need studies.

Read on Church in Need

Additional Notes

- All links were tested on September 22, 2025, and confirmed to work. If any become inaccessible, search for the title on the respective sites or use archives like Wayback Machine.

- For authenticity and details: Sources include primary texts, encyclopedias, and academic articles to ensure credibility. Statistics and events are cross-verified from multiple reliable outlets.